TOGETHER WITH COMP AI

Compliance that helps you close $1M+ deals

Comp AI helps companies get SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, or GDPR compliant in > 10 hours. It connects to your stack and keeps you audit-ready year-round, hands-off.

Teams like Dub, Strix, and Better Auth used it to unlock enterprise deals.

PLGeek readers get $2,000 off.

Please support our sponsors!

GEEK OUT

Better Editors Are a Trap (and why I’m building an alternative)

For the last year I’ve been building more and more in what you could call an agent-first way.

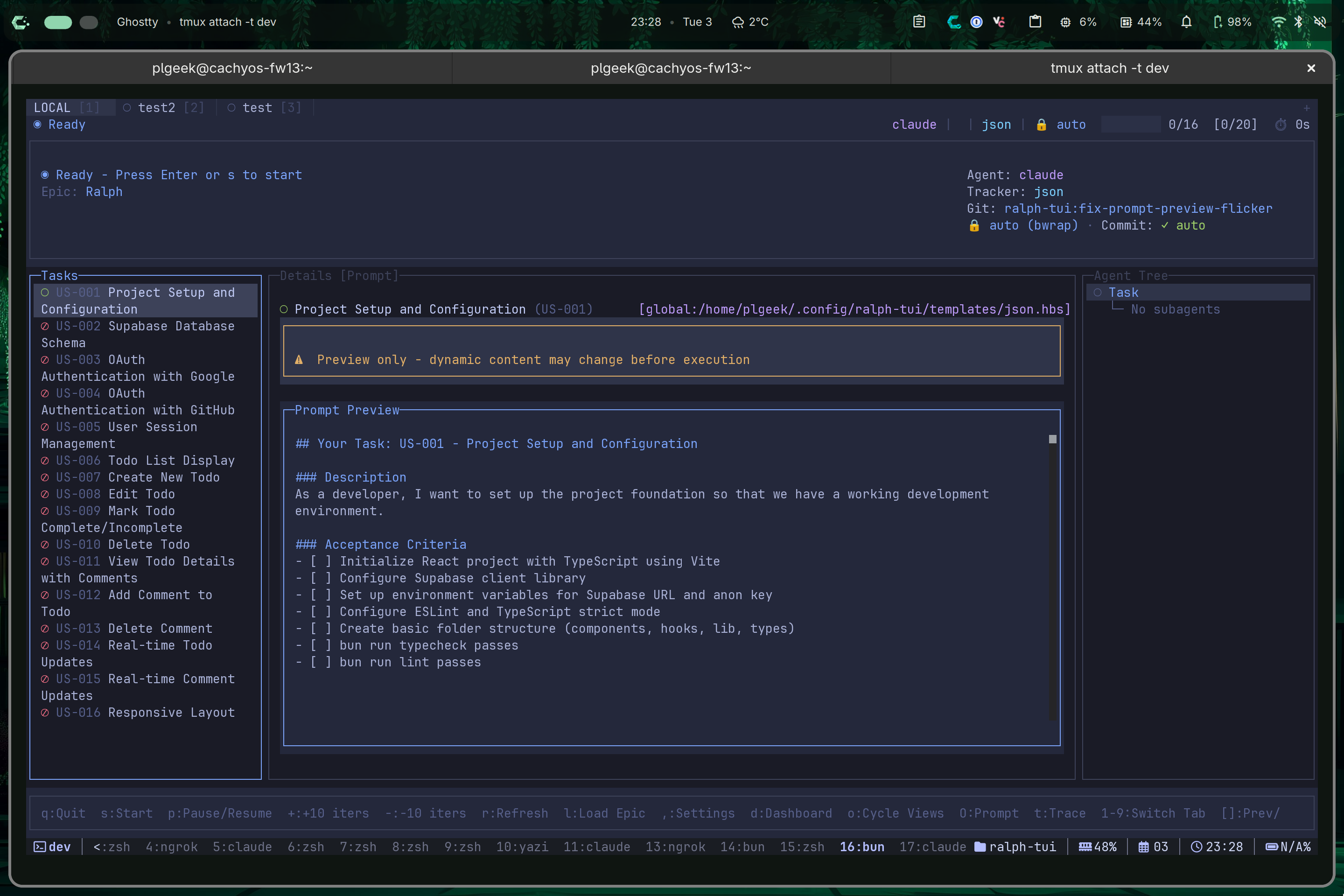

I stopped using Cursor over 9 months ago and have been living my life in the terminal. My devbox has a persistent tmux session and I ssh into it from wherever I am at the time.

Ralph TUI, my open source TUI implementation of the Ralph Loop really took off and is being used to great effect for all sorts of work, from hobby projects to commercial software.

And the strangest thing I’ve noticed is this: the more this agent-first approach works, the less the editor feels like home to me.

A year ago when I really started using Claude Code more often, I wasn’t sure how much was novelty or how much was just my mood at the time.

But it’s not a mood. It’s a shift in what you think the job is.

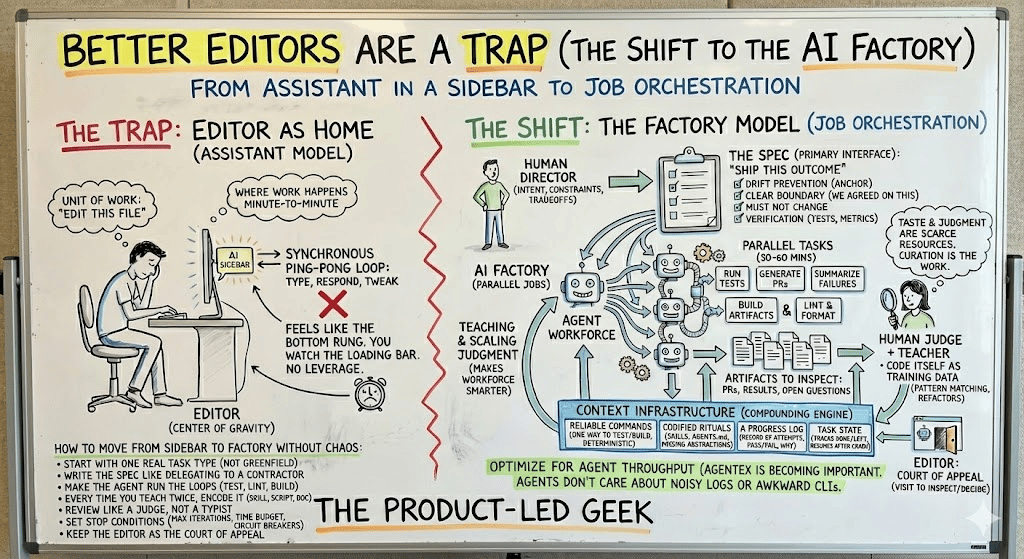

If you believe the unit of work is “edit this file,” the editor is naturally the center of gravity.

If you believe the unit of work is “ship this outcome,” the editor becomes something else: a place you visit to inspect and decide, not the place where work happens minute-to-minute.

And when I talk to other people building this way, I hear the same sentiment: the “one agent in a sidebar” pattern fairly quickly starts to feel like the bottom rung on a much bigger ladder. It’s not bad per-se, but it quietly forces you into a synchronous ping-pong loop: type, respond, tweak.

For me though, that’s exactly what agents are supposed to free us from.

The real shift is from assistant to factory

The right metaphor isn’t “AI assistant.”

It’s a factory.

Assistants are one-on-one and interactive: you’re there, they’re there, you’re watching the loop.

Factories run jobs. Many of them. In parallel. For a while. And what you get back are artifacts you can inspect: PRs, test results, summaries, open questions.

Once you can give an agent a task that genuinely takes 30-60 minutes, the dumbest thing you can do is sit there watching it in a sidebar like it’s a loading bar.

If you’re doing that, congrats, you hired a faster pair of hands and then followed them around all day.

But that’s not the leverage that we need.

In a factory model, the rhythm changes:

you write a clear brief

you send work out

you do something else

you come back and review

There's a design principle underneath this that matters: each unit of work should be stateless but informed.

The agent doesn't carry memory from the last task in its head - it starts clean every time, but with the accumulated context loaded from disk.

This is counterintuitive if you're used to long chat threads, but it's what makes the factory reliable.

A fresh agent with good context outperforms a stale agent with a long memory, because context windows degrade and confusion accumulates.

Wipe the slate, reload what matters, run again.

That’s a different product. Different UX. Different expectations.

It’s job orchestration.

And once you trust one loop, the question becomes obvious: why not ten?

Different branches, different features, running overnight.

The orchestration layer for that is what most people are missing.

And this is where “better editors” become a trap: they make the old world feel sustainable right as the underlying advantage shifts to a workflow the editor isn’t designed around.

The editor’s new job

One thing I want to be careful about: I don’t think humans are becoming irrelevant. I think the opposite.

Taste and judgment are the scarce resources.

Architectural decisions. Boundaries. What a clean abstraction is. What matters for performance vs readability. Consistency of coding standards. Product tradeoffs. UX details. The quiet decision-making that turns “it works” into “it’s good.”

That doesn’t disappear. If anything, it becomes more important, because output gets cheaper. When production is free, curation is the work.

So I’m not arguing for removing humans from the loop.

I’m arguing that the loop changes shape.

Instead of having humans as the step-by-step operators, you get:

humans as directors (sets intent, picks constraints, makes tradeoffs)

agents as spec partners (ask questions, draft, propose, stress-test)

humans as judge + teacher (locks the spec; reviews outputs; encodes lessons)

agents as workforce (execute at scale against the contract)

The editor becomes the court of appeal: where you go to inspect, debug, and resolve the hard judgment calls. It’s still important. It’s just not where you want to spend so much of your time if you’re trying to get leverage.

The spec becomes the primary interface

In the old world, the primitive is “change this file.”

In the factory world, the primitive is “ship this outcome.”

That’s why the spec starts to matter so much. It’s how you make delegation safe. It’s how you buy back your time.

A good spec needs to be specific in the ways that prevent wasted work:

what “done” means

what constraints matter (performance, style, compatibility, security)

what must not change

how we’ll verify it (tests, screenshots, metrics)

Every time I’ve seen agentic work go sideways, it’s been down to one of these two things:

The brief was vague in at least one place, and the agent confidently filled in the blank.

Drift. An agent that runs long enough without a fixed reference point will gradually shift its interpretation of the task - small misunderstandings compound across iterations until the output is technically coherent but strategically wrong.

The spec prevents this by acting as an anchor. And when you version it, you get something even more valuable: a clear boundary between "we agreed on this" and "this needs a new agreement."

That makes delegation safe over hours, not just minutes.

So we treat the spec as a freeze point.

Up to that point, chat is cheap and iterative. After that point, changes require an explicit spec revision.

The most underrated work is context infrastructure

There's a transitional phase where people obsess over manual context management: which files do I include, how do I prune threads, how do I avoid running out of context, when do I start a new conversation.

I used to think that was the skill.

Now I'm seeing it's mostly a sign your system hasn't been instrumented yet.

The stable version of this isn't to be great at babysitting context. It's to install context as infrastructure.

In practice that means four layers, all load-bearing:

Reliable commands

One obvious command to run all tests. One to lint. One to format. One to build. If there are a handful or ways to do something, an agent will thrash between them and waste entire iterations figuring out which one works. The returns on making your toolchain boringly predictable are enormous when your workforce runs hundreds of iterations overnight.

Codified rituals (skills, AGENTS.md)

Every time you find yourself telling the agent "in this repo we do X like this", you've discovered a missing abstraction. Bottle it. Write it down in a place the agent can load. Document it in AGENTS.md. Create a reusable skill.

A progress log

A plain record of what was attempted, what passed, what failed, and why. This is the agent's journal. Without it, every run starts from zero. With it, the agent (or the next agent) can read what was already tried and avoid retreading the same ground.

Task state

A structured file tracking what's done and what's left. If the loop crashes, the agent picks up where it stopped. If a task keeps failing, the pattern is visible. This is what turns a series of disconnected runs into a coherent workflow.

None of these are clever, but all of them are load-bearing. If you remove any one the agent starts repeating mistakes or re-doing work.

But the benefits compound fast.

After a month of building this infrastructure, prompting gets dramatically easier. The models may not get smarter in that time, but your codebase becomes more legible to your agent workforce which makes delegation safe.

I started optimising for agent throughput (with quality guardrails)

Here’s the part that felt slightly heretical the first time I noticed it.

Once agents become real contributors, you begin optimising for what they need.

You care less about whether a command is pleasant for a human and more about whether it’s deterministic, cheap, and produces stable outputs.

Agent Experience (AgentEx) is becoming more and more important.

Developer Experience (DevEx) is changing.

We hate noisy logs. Agents don’t.

We tend to avoid complex and awkward CLIs. Agents don’t care because they’re still scriptable.

We want perfect IDE integration. Agents don’t even know what an IDE is.

This doesn’t mean you stop caring about DevEx. It means you start making explicit tradeoffs: what do we optimise for, and where?

A few examples of where this gets concrete:

Error output becomes an interface. Agents consume error messages as their primary feedback mechanism. A human reads a stack trace and groans. An agent reads it and course-corrects (if the error is structured and actionable). You start writing descriptive assertion messages and typed error codes not for yourself, but for the agent. Clear, parseable failure output is what turns a stuck loop into a self-correcting one.

Determinism over ergonomics. Humans tolerate flaky tests because we can re-run and use judgment. Agents can't distinguish flaky from broken - a non-deterministic failure sends them down a rabbit hole trying to fix something that isn't wrong. So you start caring more about reproducibility than convenience. Pinned dependencies, seeded test data, containerised environments - things that feel like overkill for a human team become much more important for an agent workforce.

Observability over interactivity. Humans like interactive debuggers, step-through tools, rich GUI dashboards. Agents need the opposite: stdout they can grep, exit codes they can branch on, log files they can read back. You start building for observability - making the system's state legible to a process vs a person.

None of this replaces good DevEx. But it reframes what "good" means when half your contributors don't have eyes.

And it's one reason the editor gets demoted: a lot of "great editor experience" is actually friction disguised as comfort, because it keeps the human present as the runtime.

The core product becomes the feedback loops

If you only take one practical idea from all this, it’s this:

Agentic development lives or dies on feedback loops.

If your system doesn’t have cheap, reliable loops - tests, linters, type checks, preview environments, CI gates - you’ll drown in review and subtle mistakes.

You’ll feel like the agent creates cleanup work.

But if the loops are there, agent work starts to feel surprisingly safe, because the system catches the dumb stuff before you ever have to look.

And then human judgment can be spent where it’s actually valuable: the weird edge cases, the tradeoffs, the product taste.

In the old model, tests catch regressions. In the factory model, tests are the definition of done - they're what lets the loop advance without you. The agent doesn't think it's finished because it wrote some code. It's finished when the checks pass. You get reviewable work instead of cleanup work.

Every investment you make in deterministic verification directly buys you the ability to walk away.

The loop we should optimise for is teaching, not typing

Humans shouldn’t be doing mechanical steering every 30 seconds.

But we absolutely should be in the loop as a teacher and judge.

Because taste is real, and it’s learnable - at least partly - if you give the agent repeated, structured opportunities to absorb it, and the memory systems to retain it.

So the best systems don’t remove humans. They create clear teaching interfaces:

when the agent makes a questionable decision, you don’t just fix it, you explain the rule once and encode it (memory graph, lint rule, style guide snippet, skill)

when the agent’s plan is off, you correct at the planning phase, not mid-execution

when a PR is good, you label why it’s good (“matches our patterns,” “kept boundaries intact,” “nice API shape”)

Agents improve fastest when feedback has stable structure.

And there's a teaching surface most people overlook: the code itself.

Agents pattern-match against what's already in the repo. If your existing tests are clean and consistent, new tests the agent writes will tend to match them. If your abstractions are clear, the agent will follow them. If they're messy, it'll mimic the mess.

This means every refactor, every well-named function, every consistent pattern isn't just good engineering - it's training data for your workforce.

The dream is not for agents to replace our judgment.

The dream is for them to scale our judgement.

Here’s the sequence that’s worked best for me, and matches what I’m seeing from others doing this well:

Start with one real task type, not everything

Pick one recurring workflow: fix failing CI, implement a small feature, investigate a prod error, add telemetry. Don’t start with greenfield.Write the spec like you’re delegating to a competent contractor

Outcome + constraints + definition of done + how to verify.Make the agent run the loops, not you

The agent should run tests, lint, build, and summarise failures. If it can’t, you’re missing scaffolding/infrastructure.

Every time you teach something twice, encode it

Turn it into a skill, a script, a doc (e.g. AGENTS.md), a lint rule, a check. This is the compounding engine.

Review like a judge, not a typist

Spend your time on structure, taste, edge cases, product correctness - not on reformatting or catching obvious bugs.

Set stop conditions, not just start conditions.

A max iteration limit, a time budget, a rule like "if no new commit in 3 cycles, halt." Agents can get stuck in futile loops - a bug they can't solve, a flaky dependency, an ambiguous requirement they keep reinterpreting. My experience is that factories still need circuit breakers.

Keep the editor as the court of appeal

Use it when you need it, but fight its’ habitual pull.

Where this ends up

I don’t think the editor dies any time soon. But “better editor” as the main game already feels outdated to me.

We need systems that turn intent into shipped software with the least psychic overhead, by making delegation normal, verification cheap, and teaching compounding.

That’s what I’m seeing as I build more in this way.

The editor becomes a place you visit (with decreasing regularity).

The factory becomes where work happens.

And we become the source of judgment, and teachers that make the workforce smarter over time.

Enjoying this content? Subscribe to get every post direct to your inbox!

BEFORE YOU GO

Book a free 1:1 consultation call with me - I keep a handful of slots open each week for founders and product growth leaders to explore working together and get some free advice along the way. Book a call.

Sponsor this newsletter - Reach over 8000 founders, leaders and operators working in product and growth at some of the world’s best tech companies including Paypal, Adobe, Canva, Miro, Amplitude, Google, Meta, Tailscale, Twilio and Salesforce.

Check out Demand & Expand happening in SF in May (use Code PLGEEK to save 20%)

Check out our apps:

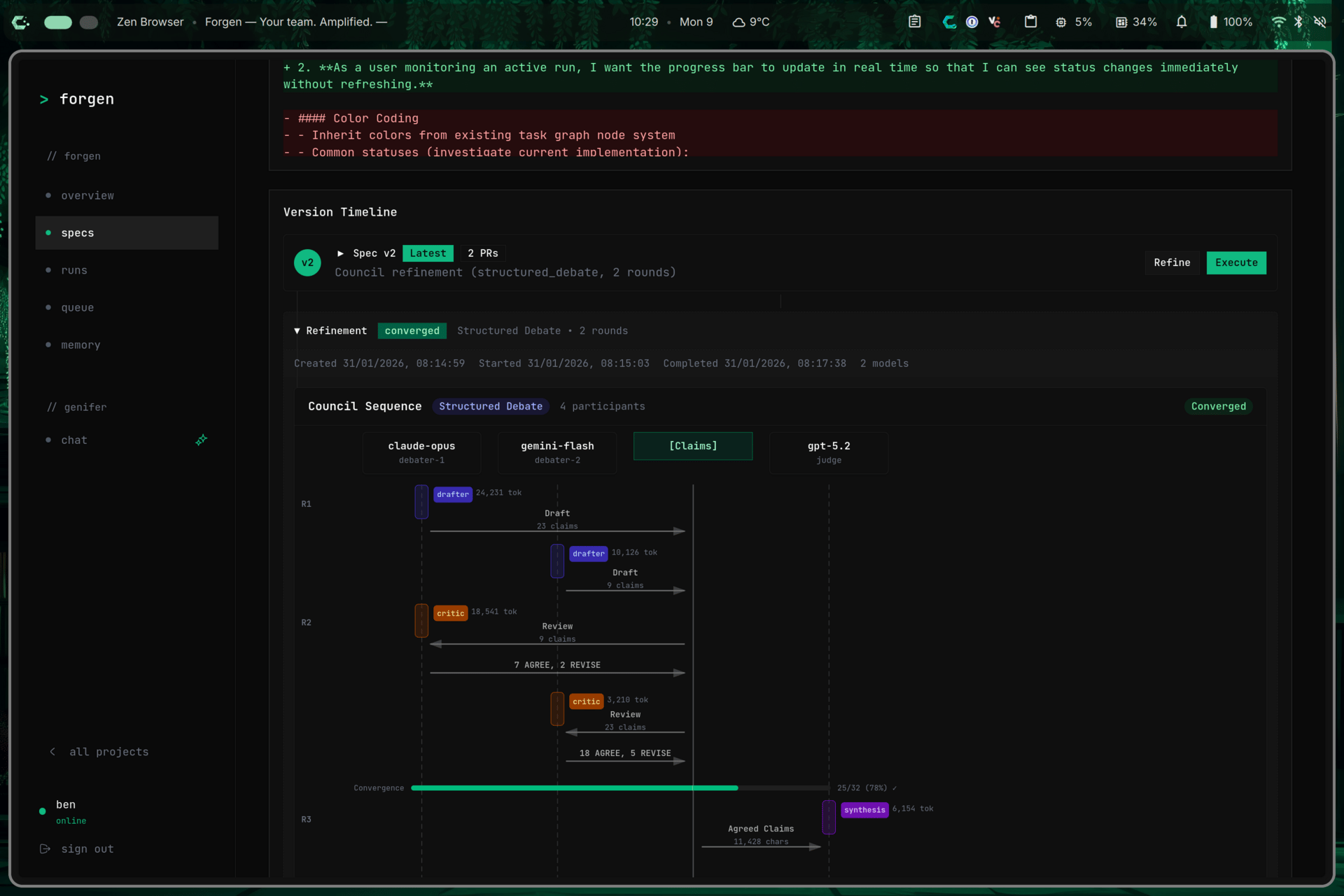

> Forgen - Multi-agent orchestration with human governance. From spec to PR.

> DevTune - Closed-loop AI search growth platform for products servings devs and other technical audiences

PS: Thanks again to our sponsor: Comp AI